The following excerpts are pulled from sections of my MSW research paper focused on understanding the ways Christianity impacts the transgender community:

Abstract

Transgender individuals raised with Christian upbringings often experience increased psychological and spiritual distress in non-affirming religious spaces. These environments can contribute to increased depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and fears of spiritual condemnation. While many transgender individuals deidentify from Christianity to protect their mental health, this can lead to a loss of belonging and experiences of complicated grief. Despite these challenges, there is limited research examining the mental health outcomes associated with Christian upbringings and deidentification among different transgender subgroups, specifically male-to-female (MTF), female-to-male (FTM), and nonbinary individuals.

In my research project, it was hypothesized that transgender groups, especially nonbinary individuals, raised with Christian upbringings would report lower life satisfaction, higher internalized stigma, and increased psychological distress. It was also hypothesized that transgender individuals who deidentified from Christianity would report improved mental health outcomes compared to those who remained Christian.

This study is a secondary analysis of the TransPop U.S. Transgender Population Health Survey (2016-2018). The original dataset included 274 transgender participants, recruited using random digit dialing and address-based sampling. For this study, a subsample of 199 transgender individuals who reported being raised in Christian environments (Protestant, Catholic, Mormon, Orthodox) were selected. Mental health outcomes such as life satisfaction, internalized stigma, and psychological distress were assessed using validated measures. Differences in mental health outcomes were analyzed by gender identity (MTF, FTM, nonbinary) using one-way ANOVAs. Multiple regressions were used to analyze the effects of Christian deidentification and gender identity on mental health variables studied.

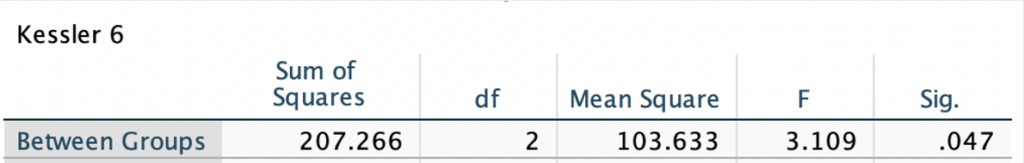

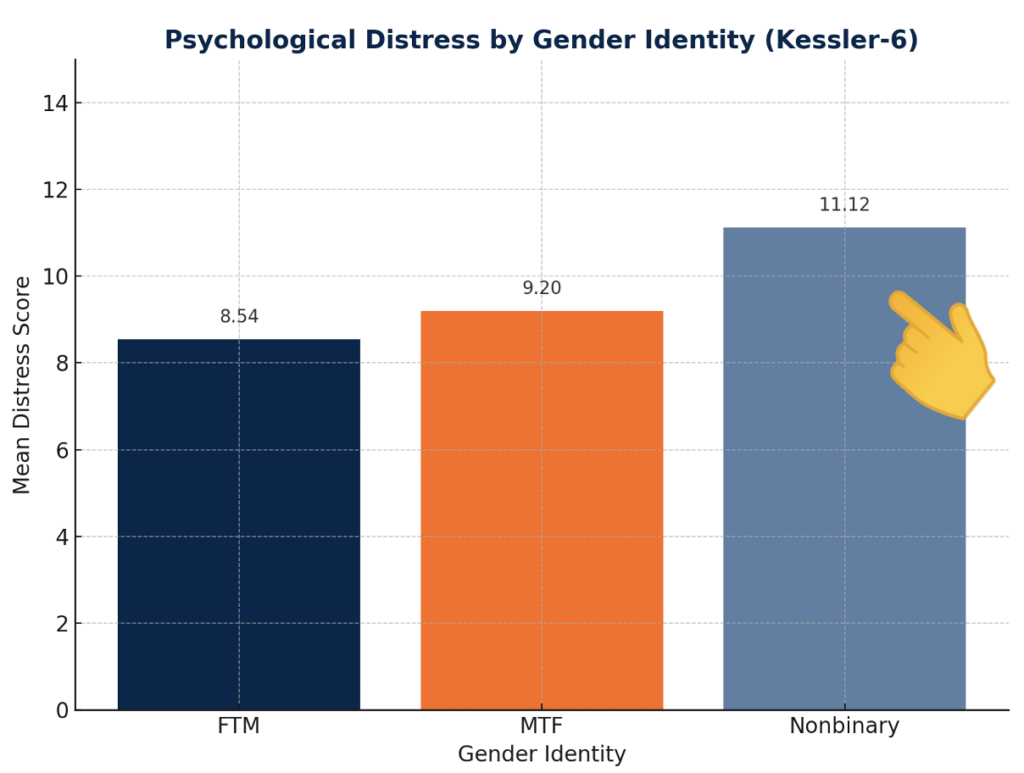

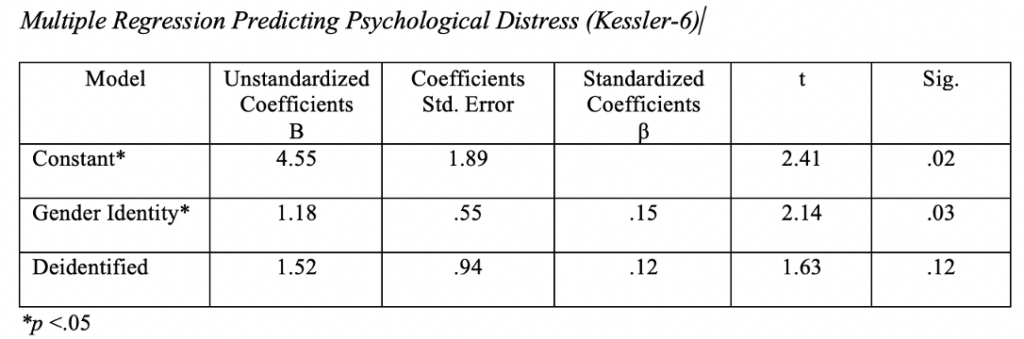

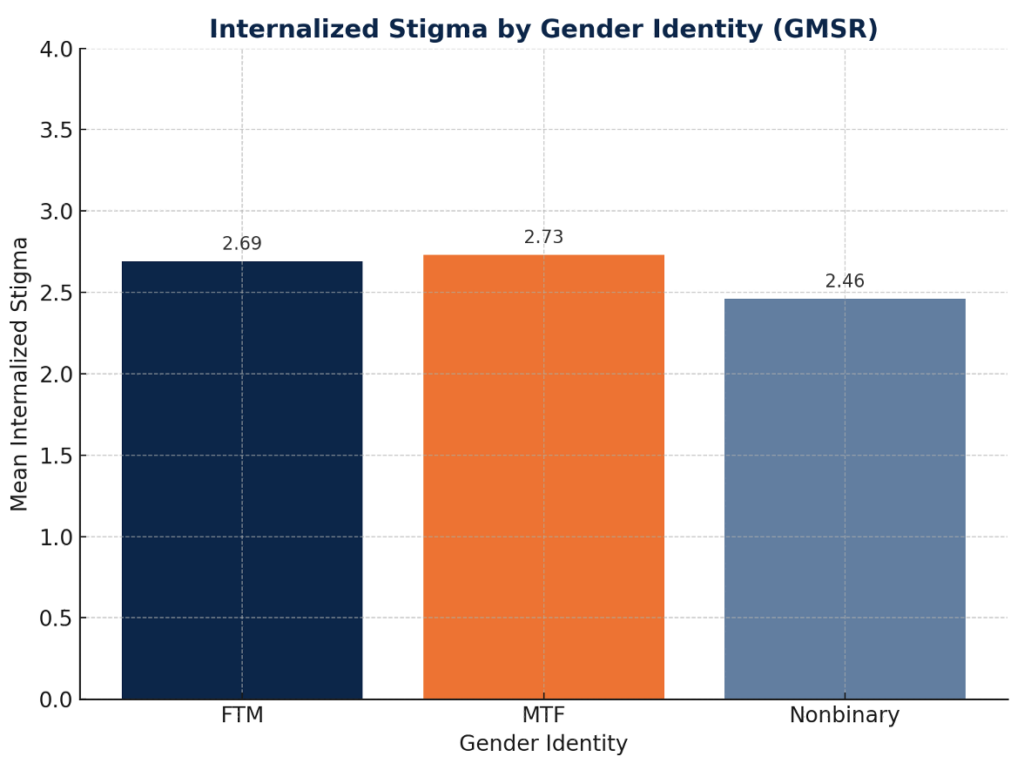

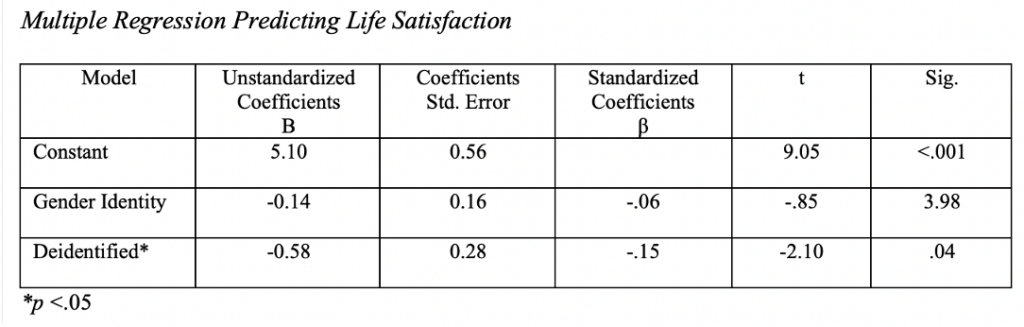

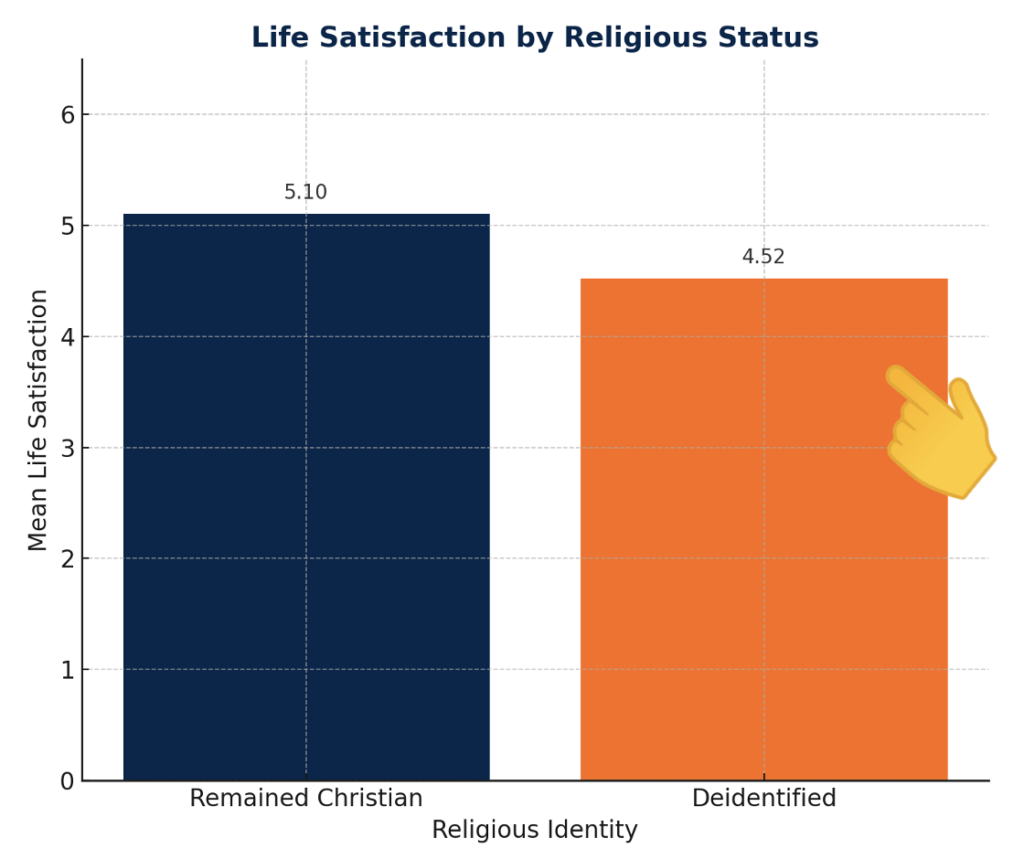

Contrary to the hypotheses, results showed no differences in life satisfaction (F(2,196) = 0.64, p = .53) or internalized stigma (F(2,189) = 1.32, p = .27) among different transgender groups. However, there was a significant difference in levels of psychological distress across transgender groups (F(2,195) = 3.12, p = .05). Post hoc tests suggested a trend toward higher psychological distress among nonbinary individuals compared to FTM individuals (p = .06). However, deidentification from Christianity did not predict lower internalized stigma (B = 0.11, p = .59) or psychological distress (B = 1.52, p =. 11). Deidentification from Christianity was significantly associated with lower life satisfaction for transgender individuals in this sample (B = -0.58, p = .04).

These findings challenge common assumptions that transgender individuals raised with Christian upbringings will experience poorer mental health outcomes. These findings also question the idea that deidentification from Christianity will improve mental health for transgender populations. Additionally, this study reveals differences in psychological well-being among different transgender subgroups.

tl;dr

This research study explored how Christian upbringings and leaving Christianity impact the mental health of transgender individuals (MTF, FTM, nonbinary). While non-affirming religious environments are often linked to psychological distress, the results of this study challenge common assumptions. No significant differences were found in life satisfaction or internalized stigma across transgender groups, but nonbinary individuals showed a trend toward higher psychological distress (especially compared to FTM individuals). Unexpectedly, deidentifying from Christianity was associated with lower life satisfaction, suggesting that leaving one’s faith may come with emotional costs despite efforts to protect mental health.

Here are some insights from different sections of the research paper:

Literature Review

Approximately 1.4 million transgender adults in the United States—about 0.6% of the adult population—identify as transgender, including MTF (33%), FTM (29%), and nonbinary (35%) individuals.

39% of transgender individuals report experiencing serious psychological distress, compared to only 5% of the general population, and can fluctuate based on stigma, shame, trauma history, discrimination, and stage of transition.

40% of transgender individuals report a suicide attempt—nearly 9 times higher than the general population. MTF and nonbinary AMAB youth report higher rates of suicidal ideation than other transgender subgroups.

Roughly 66% of transgender adults were raised in religious communities. Trans individuals raised in non-affirming Christian environments frequently experience psychological and spiritual distress leading to increased depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and fears of divine condemnation.

While many transgender individuals deidentify from Christianity to protect their mental health, this can lead to ambiguous loss, decreased belonging, and spiritual distress. Unfortunately, there is limited research examining the mental health outcomes associated with Christian upbringings and deidentification among different transgender subgroups, specifically MTF, FTM, and nonbinary populations.

Research Design

This study is a secondary data analysis of the TransPop U.S. Transgender Population Health Survey (ICPSR 37938), the first national probability sample of transgender adults in the United States. TransPop used a survey design with probability sampling—via random digit dialing & address-based sampling to recruit a nationally representative sample. Data were collected in two waves: Wave 1 (April–August 2016) and Wave 2 (June 2017–December 2018) The full sample included 274 transgender and 1,162 cisgender participants, allowing comparisons across gender identities and experiences. Ethical oversight was provided by the Gallup IRB, UCLA IRB, and several academic institutions.

Sample

This study focuses on a subsample of 199 transgender adults from the national TransPop survey who reported being raised in Christian environments (e.g., households, churches, schools). Participants were included if they were 18 or older, had at least a 6th-grade education, completed the survey in English, and identified as transgender based on responses to sex assigned at birth and gender identity.

The sample includes transgender individuals with diverse ages, sexual orientations, and gender identities with Christian upbringings, identified as: 67% Protestant, 27% Roman Catholic, 4.5% Mormon, and .5% Orthodox. Race: 70% White, 9% Black, and 9% Latino.

Measures

The independent variables (nominal) included:

Raised Christian: Based on Q212 from the TransPop survey who identified being raised Christian (n = 199); includes participants raised Protestant (n = 135), Catholic (n = 54), Mormon (n = 9), or Orthodox (n = 1).

Deidentified: Derived from Q211; participants raised Christian were coded as either currently Christian (n = 53) or deidentified from Christianity (n = 146).

The dependent variables (interval) included:

Life Satisfaction: Measured by the 5-item Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS); scores range from 5 to 35, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction with life (Cronbach’s α = .90).

Internalized Stigma: Assessed using the 6-item GMSR internalized transphobia subscale; scores range from 6 to 30, with higher scores reflecting greater internalized stigma and negative self-perception (Cronbach’s α = .86).

Psychological Distress: Measured using the 6-item Kessler-6 (K6) scale; scores range from 0 to 24, with scores ≥13 indicating serious psychological distress (Cronbach’s α = .90).

Demographics

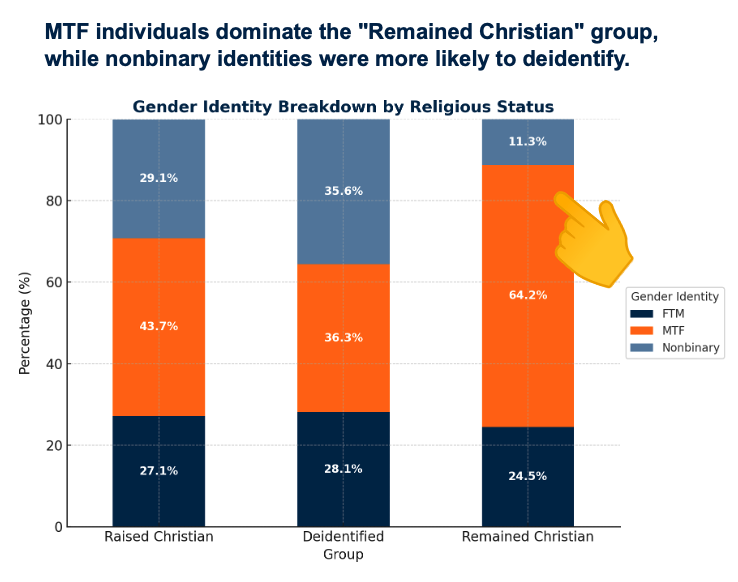

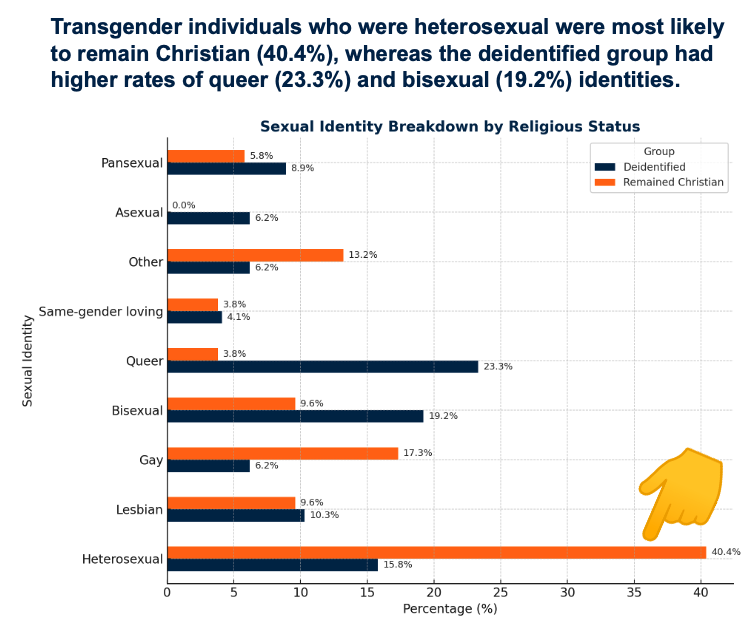

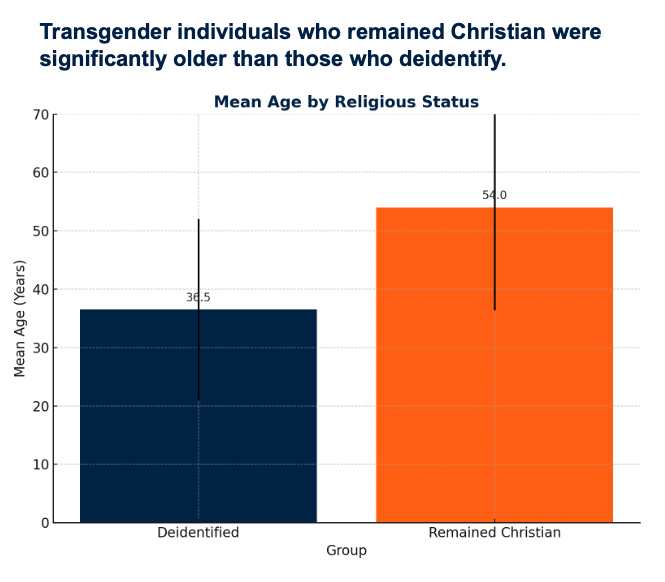

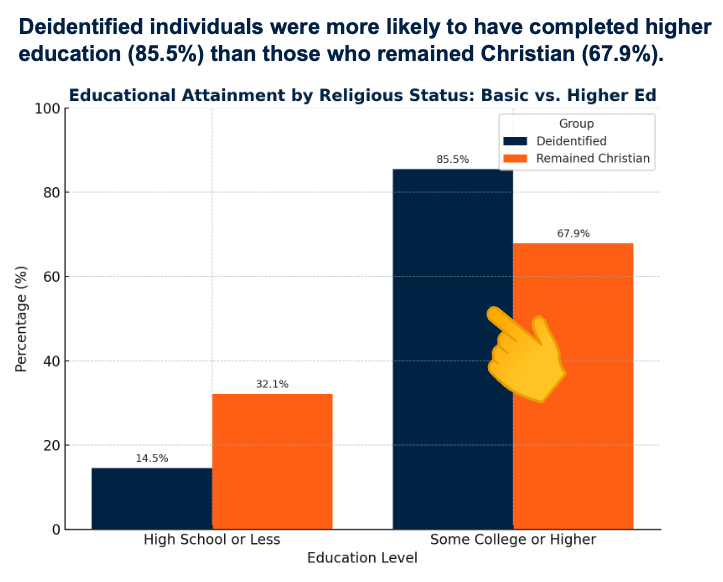

The demographic data of transgender individuals in this study who remained Christian are more likely to be MTF (64.2%), older (M = 54.00, SD = 17.64), heterosexual (40.4%), and had lower level of educational attainment, with the majority completing high school or less (32.1%) and some college (37.7%). In contrast, those who deidentified from Christianity were more likely to be nonbinary (35.6%), queer (23.3%), or bisexual (19.2%), and had a higher educational attainment with 28.3% completing college and 18.6% pursuing more than a college degree.

Here’s a look at how MTF individuals were more likely to remain Christian:

Here’s a look at the ways heterosexual transgender individuals were more likely to remain Christian:

Here’s a look at how transgender individuals who remained Christian tended to be older than those who were deidentified, suggesting generational differences.

Here’s a look at education levels and how transgender individuals with higher education tended to be more likely to deidentify from Christianity in my sample:

Psychological Distress

One-way ANOVA showed a statistically significant difference in psychological distress across gender identity groups (F(2,195) = 3.12, p = .05); nonbinary individuals reported the highest distress (M = 11.12), followed by MTF (M = 9.20) and FTM (M = 8.54).

Post hoc tests revealed a trend toward higher psychological distress in nonbinary individuals compared to FTM (p = .06).

Multiple regression analysis found that gender identity significantly predicted psychological distress (B = 1.18, p = .03).

Deidentification from Christianity was not a significant predictor of decreased psychological distress (B = 1.52, p = .12).

Internalized Stigma

One-way ANOVA revealed no significant differences in internalized stigma scores across gender identity groups (F (2,189) = 1.32, p = .27). Average internalized stigma scores were similar across groups: FTM (M = 2.69), MTF (M = 2.73), and Nonbinary (M = 2.46), with no meaningful statistical differences. Multiple regression analysis showed the model was not significant (F(2,189) = 0.99, p = .38, R² = .01), indicating gender identity and deidentification explained very little variance in internalized stigma. Neither gender identity nor deidentification from Christianity significantly predicted internalized stigma.

Life Satisfaction

One-way ANOVA showed no significant differences in life satisfaction across gender identity groups (F(2,196) = 0.64, p = .53); life satisfaction scores were relatively similar across FTM, MTF, and nonbinary individuals. FTM participants reported the highest average life satisfaction (M = 4.02), followed by MTF (M = 3.77) and Nonbinary (M = 3.66), but not statistically meaningful.

Deidentification from Christianity significantly predicted lower life satisfaction (B = -0.58, p = .04), meaning those who left Christianity reported lower satisfaction with life compared to those who remained Christian.

STRENGTHS

This study used the TransPop dataset—the first national probability sample of transgender individuals in the U.S.—and created a new “Deidentified” variable to explore how leaving Christianity may impact mental health. It also used strong, validated measures and looked at differences across MTF, FTM, and nonbinary participants to highlight mental health variations in gender identity.

LIMITATIONS

A major limitation is the small sample size (N=199) and use of a nonprobability subsample, which limits how much we can generalize the findings. The study also didn’t account for their level of religious devotion, if they were in affirming vs. non-affirming church spaces, stage of transition, or whether some participants re-identified with Christianity later in life—factors that could have made a big difference in understanding mental health outcomes.

Discussion

Social workers should not treat transgender populations as a homogenous group and recognize that transgender subgroups (MTF, FTM, Nonbinary individuals) have different lived experiences. These differences are further complicated by the way intersectional factors (race, ethnicity, immigration status, income level, educational attainment, access to gender-affirming care, exposure to discrimination) impact trans individuals differently.

The data trend in this research reveals higher distress for nonbinary populations, compared to MTF and FTM individuals, likely due to the challenges of navigating a binary-gendered society. Social workers should be prepared to offer tailored support to address the unique stressors of their nonbinary clients.

Christian upbringing was not a significant predictor of increased psychological distress or internalized stigma. Social workers should assess how their religion (or religious community) impacted them and any strengths or challenges with their belief system.

Transgender individuals who deidentified from Christianity reported significantly lower life satisfaction. Social workers and therapists should consider exploring themes of spiritual grief, loss of community, and fear of spiritual condemnation for those deidentified.

Younger transgender adults, especially those who are nonbinary, queer, or college-educated, were more likely to deidentify from Christianity. This signals a generational difference (and sexual identity difference) in Christian affiliation. Social workers should recognize that trans individuals who are LGBQ will likely be in the minority in Christian communities and may need additional support in those cisnormative and heteronormative spaces.

Future Research

Future research should explore factors beyond Christian upbringing, such as family acceptance, political environment, community support, geographic location, adverse childhood experiences, stage of transition, access to gender-affirming medical care, and role of affirming churches to better explain variations in mental health outcomes among MTF, FTM and nonbinary individuals.

Since MTF and FTM individuals often fit within the gender binary recognized in many Christian communities, it is important to explore the unique challenges faced by nonbinary individuals who may feel more excluded than binary trans peers. It would also be interesting to study impact of male privilege on mental health outcomes of FTM individuals.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank the academics, theologians, and pastors who have helped me grow in my understanding of how to better serve and love our transgender community, especially Father Shannon T.L. Kearns, for his work supporting trans men of faith and advocating for trans inclusion in the church; Austen Hartke, for his theological and practical support of transgender Christians everywhere; and Megan K. DeFranza, PhD, for advancing more inclusive biblical interpretations to affirm transgender Christians and supporting intersex believers.

If you would like a copy of the full research paper, please reach out.